Greenland: Redemption of the Nuclear Family

Does God's ultimate design hold up against the apocalypse?

The apocalypse subgenre is one that has always intrigued me. I naturally gravitate towards stories that present scenarios that either bring an end to what we know or change life enough that things will never be the same. One of the best modern examples of this subgenre takes the form of one of my favorite tabletop roleplay games, The End of the World. While it’s now unfortunately out of print, Fantasy Flight Games created what I believe to be the perfect introduction into the tabletop roleplay game world. It presents extreme apocalyptic scenarios like zombie outbreaks, alien invasions, artificial intelligence takeovers, and even a creative literal interpretation of the Book of Revelation. All of these scenarios take place in real-time, real-world settings, and the characters in the game are the players themselves. Everyone acts how they would normally act. The relationships in the game are as they are in reality. A person’s quirks, skills, and positive and negative traits are as accurate as you want them to be in the game, which provides an endless supply of drama. In most of the games I have played with my family and friends, there have been quite a few memorable moments. From laughter, to anxiety, to sorrow, the game could easily provide it all with a gamemaster who knows how to tell a story. Every game left my friends wondering what would happen if the scenarios we played out really did come true, and how terrifying it would be. What lengths would we go to save not just ourselves, but also our families?

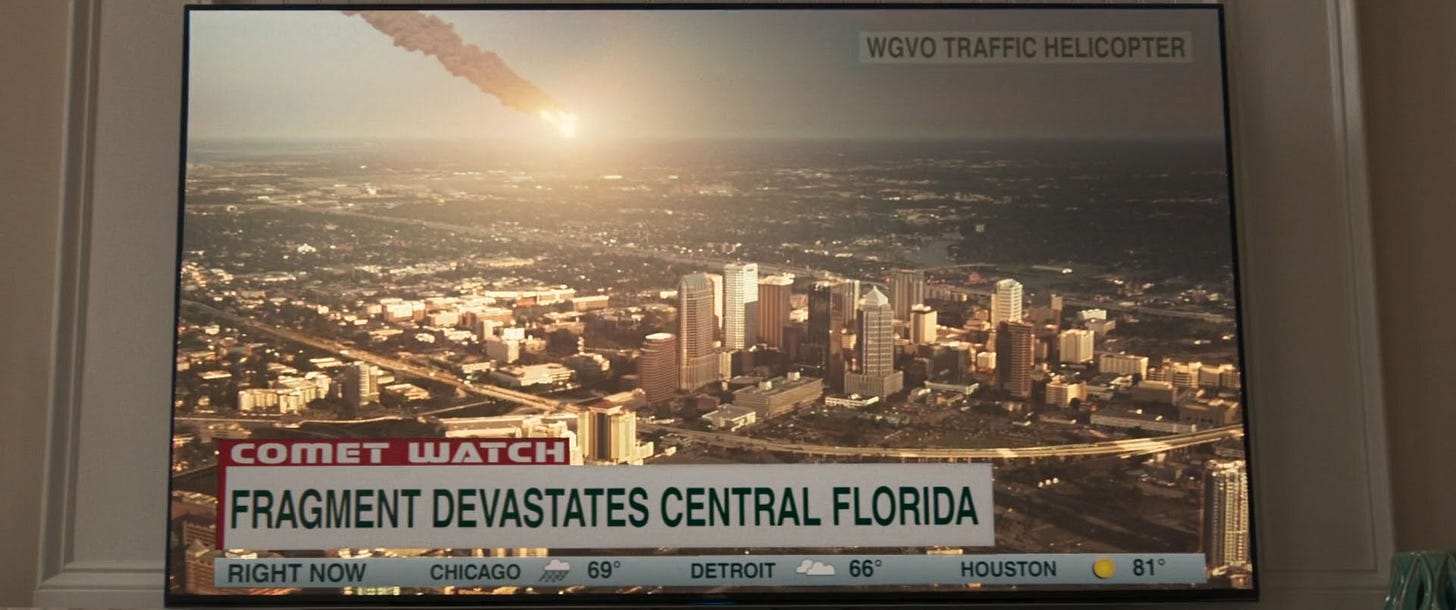

While I have unfortunately never been on the “player” side of the table - as I usually run all the scenarios we play - I’ve wondered just how anxious I would be if I was actually playing the game instead of running the show, setting up the story and conflict for my players. Last month, I believed I got a good taste of what I would be feeling as I sat, shaken, after my viewing of Ric Roman Waugh’s Greenland. The movie, starring Gerard Butler and Morena Baccarin, is about a broken family on the verge of divorce that is trying to survive “Clarke,” a comet made up of a giant cluster of space objects that is on its way to impact Earth. The family’s goal is to find shelter from the destruction, and time is running out. After the first piece of Clarke hits Earth, obliterating almost an entire state in the USA, the world finds out that there’s only about 48 hours until the “planet killer” portion of Clarke strikes, setting off an extinction event worse than the one that scientists claim killed the dinosaurs.

Greenland checked all my boxes for a memorable apocalyptic drama. As with any film, action and effects alone cannot drive a movie home into our hearts and minds. Greenland certainly has eye-opening special effects but is also smart enough to be restrained with showing them, which serves to increase the tension whenever we do see Clarke in the sky or impacting Earth. Waugh and Greenland’s writer, Chris Sparling, are also skilled enough to know that realistic human drama is what draws the viewer into a movie. Butler and Baccarin’s characters are estranged at the beginning of the film, both from each other and from life itself. Butler’s character, John Garrity, is an architect, but his opening scene shows how he is unable to focus, looking at a family photo on his phone instead of studying blueprints. A coworker must convince him to clock out for the day and go home, something that John first balks at, but eventually agrees to do. John comes home to find his wife, Allison, running in place on a treadmill, not really going anywhere but still sweating, nonetheless. While the cause for their awkwardness together is not clear at first, the subtext and body language doesn’t lie - their relationship is standing on quicksand. John genuinely brightens up when he sees his son, Nathan, and we see their bond is clearly strong, regardless of what is going on with mom and dad.

As the next scenes play out, signs of impending doom begin to multiply. After seeing military jets fly overhead when he’s out to get groceries, John receives an odd, automated call that tells him he and his family have been selected for emergency sheltering. After returning home, he tells his wife that he received the call, but as they have company over to watch the live news report showing Clarke’s first strike, they keep quiet, as there is still much uncertainty and they don’t want to excite their neighbors. After they witness the tremendous impact of Clarke’s first fragment on the news, the jig is up. Everyone knows their lives have already changed drastically, and there’s ample evidence that more change is on the way. After the Garrity’s television posts another evacuation notice addressed to their family specifically, John and Allison quickly begin packing, as their goal is now survival.

Things rapidly go south for the Garrity family as they begin their trek northward. After an emotional refusal to take the child of one of their pleading neighbors with them to safety, Greenland refuses to take a breather, subjecting its audience to scene after scene of horror, anguish, and anxiety. I felt my muscles tense as I saw frenzied riots take place at the airfield where families were packing onto C-130s for evacuation. I witnessed scenes that included gunfire erupting in the closed-quarters of a looted pharmacy, a kidnapping, a father killing to keep himself alive for his family, and many more realistic, gut-wrenching scenes. But as the time went on, the family experienced true separation. Separation from each other, from morality, from sanity, and almost, frighteningly enough, from hope. And yet, even as these things are stripped away from them, they are left with their drive, a drive for what really matters: keeping their family together. It is not solely about survival for the Garritys. Even though John and Allison were on the verge of separation before Clarke entered the picture, they are continually driven towards each other, and towards their child.

Greenland works first and foremost as a metaphor - the oncoming destruction of Clarke is certainly a stand-in for the world of loss that divorce brings upon not just the family unit, but on society itself. If it wasn’t for Clarke, the Garrity family may well have separated. For the purposes of the story, Clarke is, in a sense, divinely sent to our main characters, showing them what really matters when we’re left naked in a fallen world. I refuse to believe that the comet’s name is an accident, as Clarke is derived from the Latin name Clark, which means cleric. For those who may not know, a cleric is a member of a religious order, and are usually thought of as scribes or healers. Clarke not only played a part in healing the Garrity family, but also single handedly rewrote their story. It was divine intervention, but in an opposite way that we usually think about it. Commonly, we recognize divine intervention as God preventing or stopping a destructive force like Clarke. But at its core, divine intervention is the involvement of God (or gods, in a literary sense) in the affairs of the world.

As far as religious beliefs go, there aren’t any conversations or dialogue between John, Allison, or Nathan that are steeped with specific religious beliefs. However, we are provided revealing dialogue in a scene with Allison’s father, Dale, that helps to frame the film’s core message. As the Garrity family is planning on running for shelter again after another comet strikes, they ask Dale to come with them. As they argue with Dale at his house about his stubbornness of not wanting to leave with them, Dale finally explains his reasoning:

“My Mary went to heaven in this place. And when the good Lord’s ready for me to join her, I’m gonna be right here in this place too, bags packed.”

As the Garritys leave, Allison says what may be her last words to her father, telling him:

“Mom would have been proud. You finished the house.”

The first layer of this statement is easy to understand, as Dale had finally finished construction on the material house that he and his wife Mary lived in together. But Dale had also just seen his daughter reunited with her husband, fighting for their survival - successfully, at that - with their son. His flesh and blood had reunited as a family, here at the end of the world and against all odds. His house was truly finished, and it was built on none other than the solid bedrock of true family, and his trust in a holy God.

This idea is played out to its powerful conclusion in Greenland’s climax. As the Garrity family awaits the arrival of Clarke, John comforts Nathan in a scene that elicited many tears from my eyes:

“Listen to me, son. It’s okay. Your mom and I love you from the bottom of our hearts. We’re right here with you. So it doesn’t matter what happens, okay? Because we’re together. And we’re always going to be together. So there’s no need to be afraid.”

One might say that this statement is cheesy, carefully crafted to be the tear-jerker moment of the film, but that doesn’t concern me. What concerns me is if the statement runs coherent with the rest of the film’s message and themes. Thankfully it does, and it rings with truth. John echoes what Dale told them before they last saw him. While Dale’s “bags were packed” ready to meet the Lord and be with his wife and the rest of his family again in the heavenly realm, John understands that Dale had it right all along. The Garrity family is together again. There’s no need to be afraid because when a family is honestly, faithfully together, they’re at their strongest, and ready to take on anything, even death. They can even go up against an apocalypse and come out the other side, still standing.

Family is a concept that runs through the entire Bible. The idea and design of the family was presented at the very beginning. After God created male and female, Genesis 1:28 tells us:

“God blessed them; and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it; and rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over every living thing that moves on the earth.” (NASB)

Through His Word, God shows us that His plan for creation was for men and women to become one flesh (marry) and have children. With their children, mothers and fathers form the family unit, which in God’s mind – the very mind that created all of reality – is the essential foundation of human civilization. This stress on family is seen in the provisions of the Mosaic covenant as well, through the fifth and seventh commandments. Family is so important to God that it was codified in Israel’s national covenant, and the New Testament supports and speaks on many of the same ideas God spoke about in the Old Testament through the living Word – Jesus – along with the other famous writers the Holy Spirit inspired.

Lastly, the Bible has a different view of people, especially regarding the family structure, than what we usually understand in our modern Western cultures. We can see this in the story of Noah. When God saved Noah from the flood – an apocalyptic situation not all that different from the one seen in Greenland – salvation wasn’t individualized. Not only was Noah saved, but God saved his wife, his sons, and his sons’ wives. (Genesis 6:18) The same went for Abraham and his family. When the family unit is present, God’s covenant is familial – not individual. After all, why wouldn’t it be, since we all came from the same family unit that God created?

Should you choose to view Greenland – or even watch it again, as I did just 48 hours after my original viewing – keep Noah, his family, and the ark he built in mind as you take in the final moment of the film. When those big doors open, destruction is seen all around. Yet life is present in the form of a flying bird and the families that emerge into the light. Even after a planet killer hits home, God’s mercy and salvation is present and available, even to those who have yet to profess His name, even after all they’ve witnessed. The Son still shines. At the end of the world, the family unit lives on.

Reading your analysis makes me want to watch the movie ~ and I generally avoid apocalyptic movies.